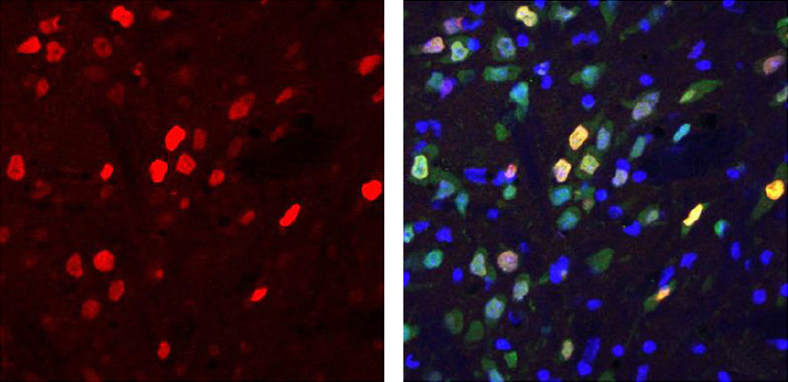

Protein production: Mice injected with a ‘mini’ version of the MECP2 gene express a fragment of the protein (red) in their neurons.

Source: [Spectrum, | October 11, 2017]

Delivering a fragment of the Rett syndrome gene, MECP2, into neurons eases features of the syndrome in mice, according to a new study. The findings appeared today in Nature1.

The MECP2 protein is a master regulator of other genes, and a lack of it leads to Rett syndrome. A portion of the protein is known to play a critical role in regulating other genes. Activating a ‘mini-gene’ that encodes only this portion in mice that lack MECP2 alleviates motor problems and underactivity, the researchers found.

The findings bolster the notion that gene therapy might ease features of Rett syndrome in people with the condition, says lead researcher Adrian Bird, Buchanan Professor of Genetics at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. “Gene therapy has gone from being something people talked about with a shrug for decades to being something people are really excited about now.”

Rett syndrome is a rare condition characterized by intellectual disability, motor problems and, often, autism. It stems from mutations that lead to low levels of functional MECP2 protein. Having too much MECP2 leads to another condition with similar features.

This means therapies aimed at boosting the protein must operate in a narrow window.

The mini-gene therapy approach could give scientists more control over levels of MECP2, Bird says. It also raises hopes for reversing features of Rett syndrome even in adulthood.

“If you restore the gene late in life, you can restore animals’ life spans and functions,” says Mriganka Sur, director of the Simons Center for the Social Brain at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The new study, he says, “is quite impressive.”

Pint-size protein:

MECP2 mutations seen in people with Rett syndrome tend to affect two segments of the MECP2 protein: one that binds to DNA marked with certain chemical tags, called methyl groups, and another that inhibits the expression of other genes. Some typical people have mutations in MECP2, but not in either of these segments.

Bird and his colleagues engineered a version of MECP2 that encodes only the two key segments of the protein. In cultured cells from mice and people, this mini-gene produces a miniature version of the protein that still binds to methylated DNA and lowers the expression of other genes.

“Only certain regions of this protein are required for it to function pretty damn well, if not perfectly,” Bird says.

The researchers then used the gene-editing tool CRISPR to create three strains of mice: one with almost the full-length version of MECP2, another with about half of the protein (including the two key segments) and another with only the two key segments.

All three strains show less anxiety than do mice that lack MECP2, the researchers found. But the mice with the shortest version of the protein have some motor and coordination problems.

The researchers then made a mouse missing the MECP2 gene in which they could turn on the mini-gene using the drug tamoxifen. With the mini-gene turned on, the tremors, motor problems and hypoactivity in these mice all become less severe.