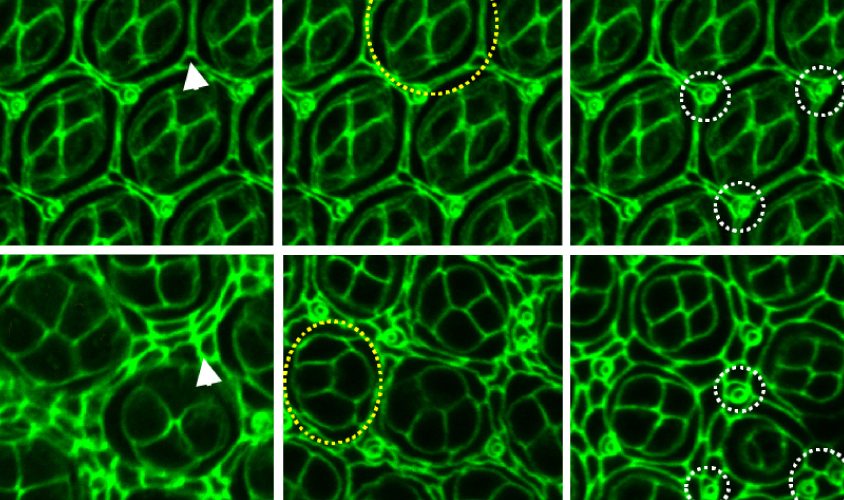

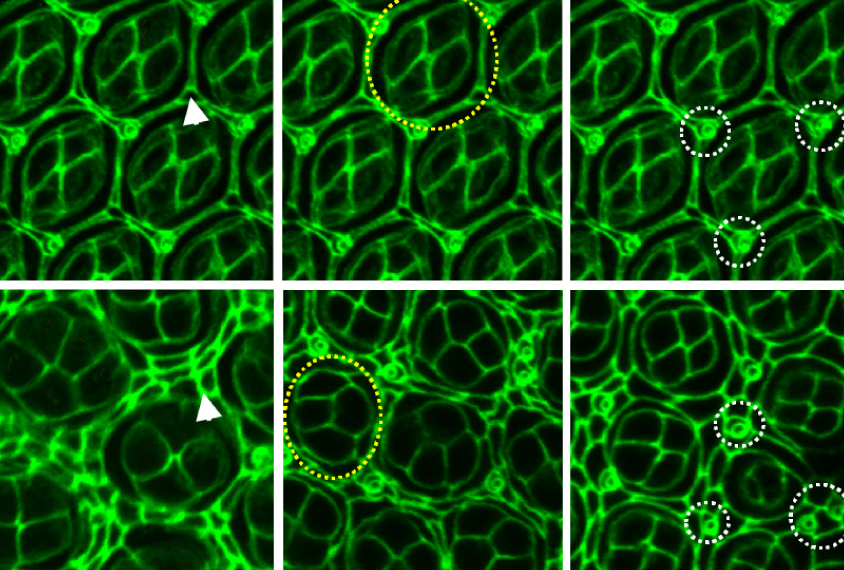

Cell scramble: Silencing fly genes akin to those on human chromosome 16 can disrupt eye development (bottom row).

Source: [Spectrum, Alla Katsnelson | ]

The absence of several interacting genes underlies the developmental problems seen in people missing a segment of chromosome 16, a new study in fruit flies suggests1.

People lacking this segment, 16p11.2, have varied features, including intellectual disability, an enlarged brain, seizures, obesity and autism.

In the new study, researchers inactivated fly genes that correspond to those within this region in people. The effect of knocking out two genes is not always equal to the combined outcome of inactivating each gene separately, they found. In many cases, the effect is less than expected, suggesting that the two genes involved collaborate in some way.

Most efforts to understand the consequences of large mutations in DNA have focused on finding a single causative gene. The new work suggests that approach is limited.

“When it comes to neuropsychiatric or behavioral development, you have to really rethink the classical model of single gene, single phenotype,” says lead investigator Santhosh Girirajan, associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Pennsylvania State University. “You should start thinking about gene interactions and how those interactions are modulated.”

The work also highlights possible interactions between genes within the deletion.

“This really is a great first step in trying to connect specific genes to having effects on development,” says Jonathan Sebat, professor of psychiatry and cellular and molecular medicine at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the work. “[The study] generates a lot of hypotheses about which genes are important and in which combinations.”

Double trouble:

Girirajan and his colleagues identified 14 genes in fruit flies that are orthologs of genes within 16p11.2 in people. (People have an additional 11 genes in the region.)

The researchers first knocked down each of these genes, either throughout the fruit fly or in only the eye, wing or nervous system. They used a technique called RNA interference, which relies on RNA molecules to silence specific genes.

The single-gene knockdowns produce a variety of effects: Nervous system deletions tend to lead to motor problems, for example. Other knockdowns cause seizures and disrupt neuronal growth; some are lethal.

The researchers then chose four genes that, when silenced, have the most severe effects on the flies. They knocked out each one of these genes, in combination with knockdowns of each of the other 13 genes in the eye. Of these 52 paired knockdowns, 20 produce effects that differ from the combined effects of each gene on its own.

For example, inactivating the gene MAPK3 alone causes cells in the eye to be disordered. Silencing a second gene, C16ORF53, restores normal eye development. This suggests that the genes are modulating each other in a complex way, Girirajan says.

The interactions are not limited to genes within the 16p11.2 region: The researchers identified 18 fly genes that correspond to human genes involved in brain development and 32 associated with neurological conditions. They knocked down these genes along with one of four corresponding fly genes. In 52 of those 222 pairs, the effect of the paired knockdown differs from that of each knockdown combined.