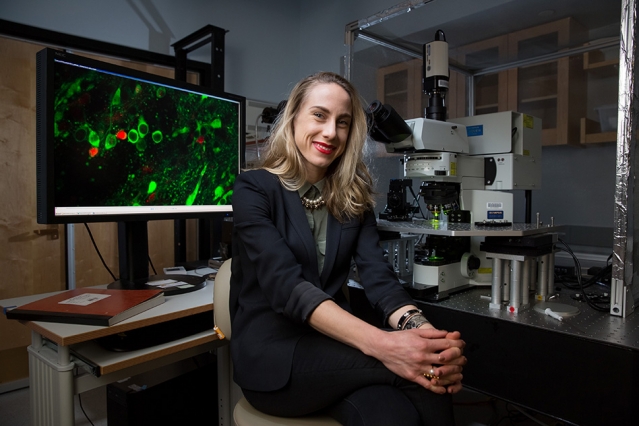

Polina Anikeeva was born in Leningrad, USSR, but grew up in St. Petersburg, Russia – the same city, whose name reverted to its original form after the fall of the Soviet Union. While in school there, she encountered two inspiring scientists who helped propel her toward a career at MIT, where she now develops cutting-edge materials to help researchers probe the mysteries of the brain in unprecedented ways. Image: Bryce Vickmark

Polina Anikeeva explores ways to make neural probes that are compatible with delicate biological tissues.

Source: [MIT News Office, David L. Chandler | February 18, 2018]

Polina Anikeeva was born in Leningrad, USSR, but grew up in St. Petersburg, Russia; the city’s name reverted to its original form after the fall of the Soviet Union. While in school there, she encountered two inspiring scientists who helped propel her toward a career at MIT, where she now develops cutting-edge materials to help researchers probe the mysteries of the brain.

Anikeeva’s parents are both engineers, and she became interested very early on in figuring out how to make things that hadn’t been made before. She has pursued that passion through all her work — as the Class of 1942 Associate Professor in Materials Science and Engineering and in her other activities. She has been an active climber and runner (she ran her third Boston Marathon last year), and as an avid artist she occasionally creates paintings to illustrate her scientific research or help her students visualize scientific concepts.

One of her earliest influences, she says, was Mikhail Georgievich Ivanov, the founder of a small math and science magnet school she attended in St. Petersburg, and her physics teacher there. “He was just a brilliant physics teacher and educated a lot of scientists who are now scattered across the world. He was a scientist himself and had worked in a research lab. But then he realized that his real passion and talent was educating kids,” she recalls.

She met her next significant mentor during her years as an undergraduate at the St. Petersburg State Polytechnic University, when she worked with Tatiana Birshtein, a professor of polymer physics at the Institute of Macromolecular Compounds of the Russian Academy of Sciences. “She was generous and adventurous enough to essentially get me a UROP position in her lab. And I had no idea how prominent she was, but as time went on it became clear that she’s actually one of the pioneers of polymer physics and went to win the L’Oréal-UNESCO Award for Women in Science the same year as Millie Dresselhaus. … So I got really lucky to work with someone of that stature very early on.”

From there, Anikeeva spent her senior year at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and then went on to an internship at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, where her work took a turn, introducing her to spectroscopy, nanomaterials, and quantum dot solar cells. As she was trying to decide between graduate programs in physics or chemistry, she met an intern from MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and decided to try that as a way of combining those fields. She completed her doctorate at MIT in materials science and engineering, and last year earned tenure as an associate professor in that department.

“It was very clear that I should go to MIT,” she says, “not because the faculty were really smart — faculty are pretty smart everywhere. It was because the students were really inspiring. They were really committed to their research but also had a really broad understanding of what is going on around them, from a research perspective and also from how it builds into the real world. … I wanted to be surrounded by really remarkable people.”

One of those people she met at MIT was to become her partner: a fellow faculty member, Warren Hoburg, who was in the aeronautics and astronautics department. While their relationship was very convenient with both of them working at MIT, she says, it suddenly became more complicated last year, when he was selected as part of NASA’s 2017 class of new astronauts. Now, “we’ll have to commute between Houston and Boston,” she says.

Soon after earning her PhD working with light-emitting quantum dots, Anikeeva determined that she was not interested in research aimed at making incremental improvements. “What I really wanted to do was not just improve devices that exist. I wanted to build devices that didn’t exist,” she says. She decided that biology was an area where a materials scientist could make significant contributions in developing new devices that could have a direct benefit for humanity.